By the Numbers: These are the social media apps Americans use most for news

But few people actually head to social media looking for news.

Half of all Americans get at least some of their news from social media sites, according to the Pew Research Center. But where they get that news can vary quite significantly — and many of them don’t go to social media apps hunting for news.

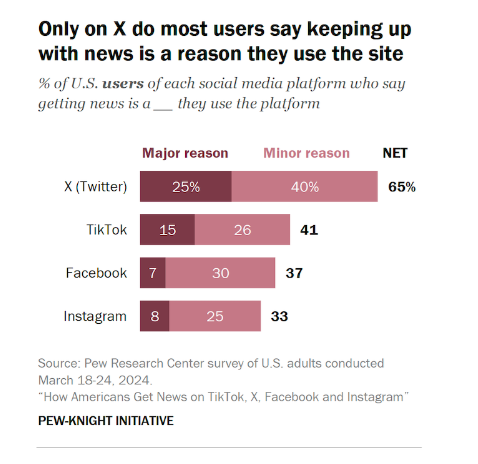

Despite major changes to X over the last year and a half since its purchase by Elon Musk, the site formerly known as Twitter remains the only social media platform where a majority of users go specifically in the hopes of finding news. But only 25% say it’s a major reason they use the app, while 40% say it’s a minor reason. So, even on the newsiest app, most people aren’t primarily scrolling for headlines.

Compare that with TikTok, where only 41% of users are looking for news at all and only 15% consider it a major reason to be on the app.

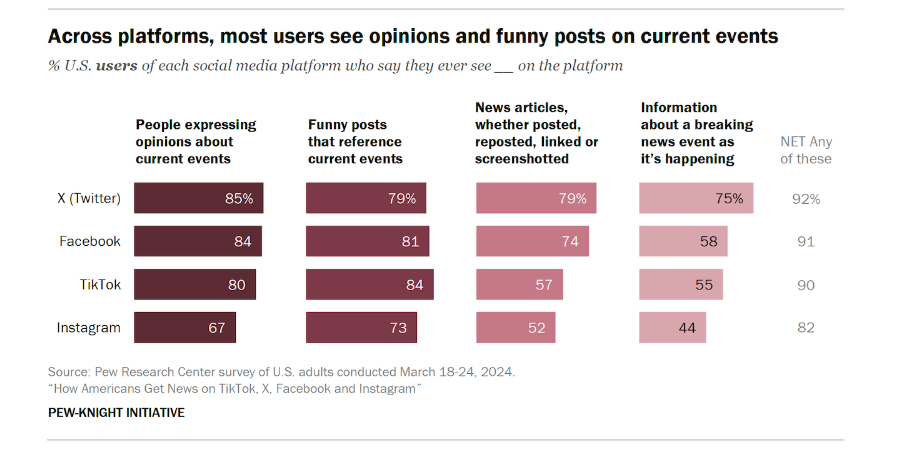

But whether users are looking for news or not, they’re likely to find it on all four of these social platforms. On every platform save Instagram, more than 90% of users say they see news-related content on the platforms. And on Instagram, the number is still 82% — a significant majority.

In some ways, the continued proliferation of news on these platforms is surprising. In several cases, it’s not at all what the app owners want.

Meta, which owns both Facebook and Instagram, has for years been distancing itself from news content. In Facebook’s early days, it was a major driver of site traffic for news sites and partnered and invested with many. But over the years, as politics became more divisive and news sites began to want to get paid for their work, Meta began to deprioritize the content in its algorithms.

As much as Threads tries to copy the glory days of Twitter, the Meta-run text social media app has made it clear it doesn’t want to make news a centerpiece. “Politics and hard news are inevitably going to show up on Threads — they have on Instagram as well to some extent — but we’re not going to do anything to encourage those verticals,” Instagram and Threads head Adam Mosseri said shortly after Threads’ launch. Similarly, Instagram quietly launched an opt-out feature that hid accounts that are “likely to mention governments, elections or social topics that affect a large group of people and/or society at large.”

Under Musk’s leadership, X has been notoriously anti-journalist. He changed the meaning of the blue checkmark that used to be a sign of verification and trust to a signal of payment, labeled NPR as “state-owned media,” though it didn’t meet his own site’s definition, and generally antagonized mainstream media outlets.

In other words, no one really wants news on their platform, and many users don’t want it either. But it’s still there regardless.

Which means there are opportunities for PR professionals.

But we also must explore the question of what is news as the general public defines it?

A trailer for a new movie could be defined as news, or it could be an advertisement. A meme about how no one wants to work anymore could be considered a joke or a political statement.

We don’t have precise answers to this question, but Pew did ask users about four kinds of content it deemed news and whether they’ve recently seen them on these social platforms.

Unsurprisingly, the most common posts are either jokes or personal opinions rather than what a PR professional might traditionally consider news. In particular, X and Facebook are hotspots for personal opinions, while people love to crack jokes on TikTok. News articles are scarcer, especially on the image-driven apps of TikTok and Instagram. And only X sees a significant amount of real-time news sharing, certainly driven in large part by its ability to sort timelines chronologically.

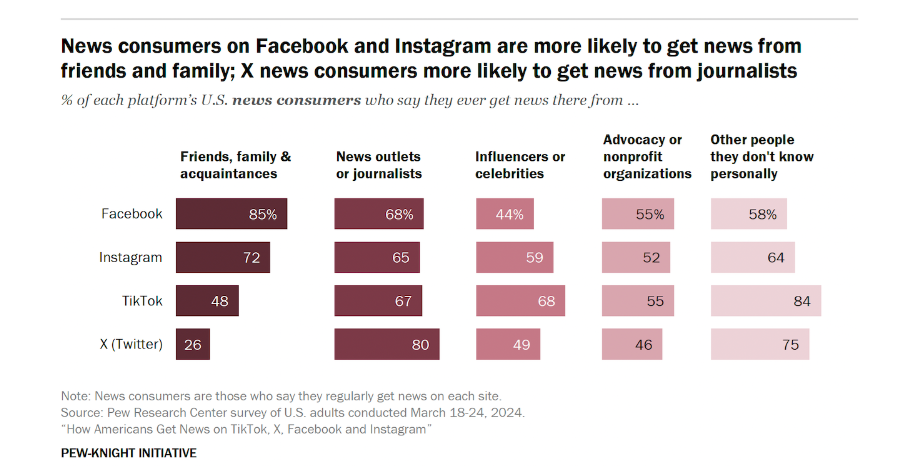

Finally, a great deal of this news content, including opinions and memes, aren’t coming from classic news sources. They’re coming from friends and family.

Some of these patterns make sense: people on Facebook are more likely to know the people they’re friends with personally compared to the more anonymous followings on X, so naturally they see more content from friends than news sources. But we still do see a surprisingly strong showing from news outlets and journalists, including on the Meta platforms that have tried to discourage news content.

What it means for PR professionals

First and foremost, it means that news of X’s death has been exaggerated. Data suggests that its userbase may have declined by up to 30% YOY, but those who are still there are news die-hards. That means they could be very receptive to your brand’s news or media hits on the platform. Of course, that must be weighed against the brand safety risks that have arisen on X.

It also means that PR professionals should think creatively about what news is and how to present it. Even serious news can be memefied or be presented in a visual format that can gain eyeballs without being clocked as old-school news. There is still room for news on all platforms — it just might look different than you’re accustomed to.

Reaching consumers in today’s media environment is more challenging than ever. But with a bit of creativity and data, it can be done.

Allison Carter is editor-in-chief of PR Daily. Follow her on X or LinkedIn.